After a career in minor league baseball, he found fame with the precocious canines who starred in the popular Canadian TV series

The star of the heartwarming Canadian television series The Littlest Hobo was a dog who showed an uncanny knack for arriving at a time of peril. After performing heroics, the shrewd stray resisted entreaties to stay, preferring instead the open road.

The vagabond canine - in truth, several look-alike German shepherds - was handled by Chuck Eisenmann, himself a wandering spirit.

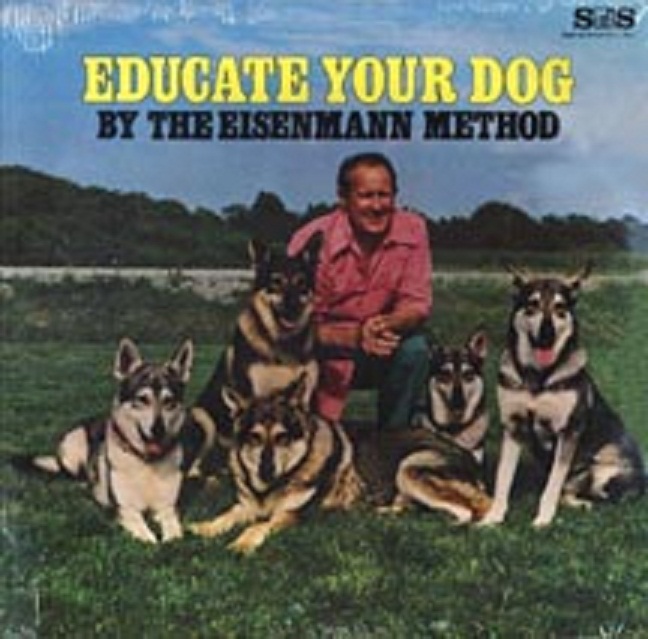

Eisenmann, who died on Sept. 6 in Roseburg, Ore., spent decades promoting what he described as a unique, modern method for teaching animals - four-legged performers and their two-legged owners alike. He rejected the word trainer, preferring instead to be thought of as an educator.

"Any dog has the seeds of genius," he pronounced. "The educated dog has the power to reason and to act on the conclusions reached."

Accompanied by his pack, he made thousands of personal appearances to promote his technique, as well as the movies in which the dogs starred.

His promotional material promised "the world's greatest intellectual dogs! Hear them talk, add, subtract! See them do feats of intelligence! See the world's only dog with a 5,000-word vocabulary in three languages!"

By the late 1960s, Eisenmann was a guest on television talk shows, appearing on The Steve Allen Show with the comedian Henny Youngman and the folk-rock band the Youngbloods.

In 1972, he conducted a demonstration for the benefit of the psychology club at the University of British Columbia, as recounted in Weekend Magazine.

He commanded his dog, London, to jump into the air.

The dog jumped.

"This time, London, when I say 'jump' it will mean lie down and put your paws over your eyes ... London, jump!"

The dog dutifully lay down and covered its eyes.

He expounded on his theories in a series of softcover instruction guides with such titles as Stop! Sit! and Think and A Dog's Day in Court.

Before finding fame as a dog expert, he owned a nightclub, worked as a sports editor, enlisted in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and served as commandant and athletic director of a military school. Four years of military service during the Second World War interrupted a professional baseball career that included pitching for teams in Ottawa and Vancouver.

Charles Paul Eisenmann was born on Sept. 22, 1918, in Hawthorne, Wis. After graduating from high school, he joined the peacetime U.S. Army at the age of 18.

A gifted athlete, the right-hander pitched for a service team in Hawaii, according to research by the baseball historian Gary Bedingfield. Scouts noticed the 6-foot-1, 195-pound hurler with a looping curveball, and he was signed to a contract, beginning his pro career with the Henderson Oilers of the Class-C East Texas League.

A stint with the Vancouver Capilanos, a Class-B team, the following summer led to an eventual promotion to the old San Diego Padres, two levels below the majors. He pitched in just three games before swapping his red-and-white flannel uniform for army greens five months after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

In 1943, having graduated from officer school, the second lieutenant pitched for the Signal Monarchs in an eight-team league featuring American, Canadian and British soldier athletes in London.

He followed the Allied armies through northwestern Europe after having organized in Paris the first baseball game to be played on liberated French soil.

After returning stateside several months after the war, he resumed his playing career in the high minor leagues. After three seasons, he gained his reward with a promotion to the Chicago White Sox at the end of the 1948 campaign. But he was not called on to pitch before season's end and, as it turned out, sitting on the bench at Comiskey Park was as close to a major league appearance he ever made.

He pitched in 17 games for the Ottawa Giants in 1951, another way station in a career that also saw him play in Louisianna, Washington state, Oklahoma, Tennessee, New York, Alabama and California.

At 34, he was released, though he refused to give up the game. He worked briefly as an umpire in California and took turns on the mound for semiprofessional teams in Nebraska and North Dakota.

It was while operating a nightclub in the offseason that he got his first dog, which he named London after the city that had so bravely faced down the Nazis. Ever after, his top dog carried that name. The dog accompanied him to the ballpark in summers. One newspaper account described London's panoply of tricks: "The dog brought keys from Eisenmann's car, bowed to the crowd, brought a bat and a broom to the pitcher, ran the bases, brought a ball bag from the mound, told how old he is (five), imitated a kangaroo, closed a door, turned out a light, played dead, untied a boy and did a little typewriting."

In 1955, with his master managing the Kearney Irishmen, London was sent onto the field during a game to bring a warmup jacket to the pitcher, who had reached first base. The dog mistakenly went to the pitching mound before spotting the pitcher and completing the delivery. But the delay caused the other team to protest and the umpires banished Eisenmann and London from the field.

The rhubarb attracted the attention of Life magazine, which devoted a two-page spread to the pair.

In turn, the article was noticed by Dorrell and Stuart McGowan, brothers who had in mind an idea about the adventures of a homeless dog. The Littlest Hobo, a movie released in 1958, told the story of a stray who befriends a boy and rescues his pet lamb from a date with the slaughterhouse.

This was followed two years later by My Dog, Buddy, starring London in the title role in a story of "a huckleberry-faced boy and his dog."

London and younger understudies Toro and Thorn starred in two other movies, The Marks of Distinction and Just Between Us, the latter in which a dog jumps from a trestle and leaps onto the wing of a taxiing airplane.

In 1963, the CTV network added to its schedule a new show, also named The Littlest Hobo. It was billed as an adult action series, airing in the early evening. The program got solid reviews and found a global audience in syndication. The series, which lasted three seasons, was filmed at the Hollyburn Film Studios in West Vancouver and other locales in British Columbia.

The altruistic Alsatian rescued a prospector from death in the desert, thwarted a bank robbery and stopped another dog from attacking a politician on the command of his evil owner, portrayed by Eisenmann. Along the way, London befriended a Cuban refugee, an ex-prize fighter, a lumberjack, a bronco rider, a nightclub singer, the owner of a Chinese restaurant, and a deaf and mute aboriginal boy. Then the hobo would drift along to the next town, riding the rails to adventure.

The series was revived in 1979 for a six-season run. By now, Eisenmann had seven dogs (two of them female) to satisfy a hectic schedule. The series, filmed in Ontario, attracted such actors as a teenaged Mike Myers and the venerable Al Waxman. It was syndicated to more than 40 countries.

Eisenmann had a simple philosophy to explain his success with dogs: "A dog thinks just as a human does, and if you treat him as a stupid animal eventually he will act that way. That's why I act positive around my dogs and treat them as friends."

Eisenmann leaves two daughters, four grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and a sister.

After a career in minor league baseball, he found fame with the precocious canines who starred in the popular Canadian TV series

The star of the heartwarming Canadian television series The Littlest Hobo was a dog who showed an uncanny knack for arriving at a time of peril. After performing heroics, the shrewd stray resisted entreaties to stay, preferring instead the open road.

The vagabond canine - in truth, several look-alike German shepherds - was handled by Chuck Eisenmann, himself a wandering spirit.

Eisenmann, who died on Sept. 6 in Roseburg, Ore., spent decades promoting what he described as a unique, modern method for teaching animals - four-legged performers and their two-legged owners alike. He rejected the word trainer, preferring instead to be thought of as an educator.

"Any dog has the seeds of genius," he pronounced. "The educated dog has the power to reason and to act on the conclusions reached."

Accompanied by his pack, he made thousands of personal appearances to promote his technique, as well as the movies in which the dogs starred.

His promotional material promised "the world's greatest intellectual dogs! Hear them talk, add, subtract! See them do feats of intelligence! See the world's only dog with a 5,000-word vocabulary in three languages!"

By the late 1960s, Eisenmann was a guest on television talk shows, appearing on The Steve Allen Show with the comedian Henny Youngman and the folk-rock band the Youngbloods.

In 1972, he conducted a demonstration for the benefit of the psychology club at the University of British Columbia, as recounted in Weekend Magazine.

He commanded his dog, London, to jump into the air.

The dog jumped.

"This time, London, when I say 'jump' it will mean lie down and put your paws over your eyes ... London, jump!"

The dog dutifully lay down and covered its eyes.

He expounded on his theories in a series of softcover instruction guides with such titles as Stop! Sit! and Think and A Dog's Day in Court.

Before finding fame as a dog expert, he owned a nightclub, worked as a sports editor, enlisted in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, and served as commandant and athletic director of a military school. Four years of military service during the Second World War interrupted a professional baseball career that included pitching for teams in Ottawa and Vancouver.

Charles Paul Eisenmann was born on Sept. 22, 1918, in Hawthorne, Wis. After graduating from high school, he joined the peacetime U.S. Army at the age of 18.

A gifted athlete, the right-hander pitched for a service team in Hawaii, according to research by the baseball historian Gary Bedingfield. Scouts noticed the 6-foot-1, 195-pound hurler with a looping curveball, and he was signed to a contract, beginning his pro career with the Henderson Oilers of the Class-C East Texas League.

A stint with the Vancouver Capilanos, a Class-B team, the following summer led to an eventual promotion to the old San Diego Padres, two levels below the majors. He pitched in just three games before swapping his red-and-white flannel uniform for army greens five months after the attack on Pearl Harbor.

In 1943, having graduated from officer school, the second lieutenant pitched for the Signal Monarchs in an eight-team league featuring American, Canadian and British soldier athletes in London.

He followed the Allied armies through northwestern Europe after having organized in Paris the first baseball game to be played on liberated French soil.

After returning stateside several months after the war, he resumed his playing career in the high minor leagues. After three seasons, he gained his reward with a promotion to the Chicago White Sox at the end of the 1948 campaign. But he was not called on to pitch before season's end and, as it turned out, sitting on the bench at Comiskey Park was as close to a major league appearance he ever made.

He pitched in 17 games for the Ottawa Giants in 1951, another way station in a career that also saw him play in Louisianna, Washington state, Oklahoma, Tennessee, New York, Alabama and California.

At 34, he was released, though he refused to give up the game. He worked briefly as an umpire in California and took turns on the mound for semiprofessional teams in Nebraska and North Dakota.

It was while operating a nightclub in the offseason that he got his first dog, which he named London after the city that had so bravely faced down the Nazis. Ever after, his top dog carried that name. The dog accompanied him to the ballpark in summers. One newspaper account described London's panoply of tricks: "The dog brought keys from Eisenmann's car, bowed to the crowd, brought a bat and a broom to the pitcher, ran the bases, brought a ball bag from the mound, told how old he is (five), imitated a kangaroo, closed a door, turned out a light, played dead, untied a boy and did a little typewriting."

In 1955, with his master managing the Kearney Irishmen, London was sent onto the field during a game to bring a warmup jacket to the pitcher, who had reached first base. The dog mistakenly went to the pitching mound before spotting the pitcher and completing the delivery. But the delay caused the other team to protest and the umpires banished Eisenmann and London from the field.

The rhubarb attracted the attention of Life magazine, which devoted a two-page spread to the pair.

In turn, the article was noticed by Dorrell and Stuart McGowan, brothers who had in mind an idea about the adventures of a homeless dog. The Littlest Hobo, a movie released in 1958, told the story of a stray who befriends a boy and rescues his pet lamb from a date with the slaughterhouse.

This was followed two years later by My Dog, Buddy, starring London in the title role in a story of "a huckleberry-faced boy and his dog."

London and younger understudies Toro and Thorn starred in two other movies, The Marks of Distinction and Just Between Us, the latter in which a dog jumps from a trestle and leaps onto the wing of a taxiing airplane.

In 1963, the CTV network added to its schedule a new show, also named The Littlest Hobo. It was billed as an adult action series, airing in the early evening. The program got solid reviews and found a global audience in syndication. The series, which lasted three seasons, was filmed at the Hollyburn Film Studios in West Vancouver and other locales in British Columbia.

The altruistic Alsatian rescued a prospector from death in the desert, thwarted a bank robbery and stopped another dog from attacking a politician on the command of his evil owner, portrayed by Eisenmann. Along the way, London befriended a Cuban refugee, an ex-prize fighter, a lumberjack, a bronco rider, a nightclub singer, the owner of a Chinese restaurant, and a deaf and mute aboriginal boy. Then the hobo would drift along to the next town, riding the rails to adventure.

The series was revived in 1979 for a six-season run. By now, Eisenmann had seven dogs (two of them female) to satisfy a hectic schedule. The series, filmed in Ontario, attracted such actors as a teenaged Mike Myers and the venerable Al Waxman. It was syndicated to more than 40 countries.

Eisenmann had a simple philosophy to explain his success with dogs: "A dog thinks just as a human does, and if you treat him as a stupid animal eventually he will act that way. That's why I act positive around my dogs and treat them as friends."

Eisenmann leaves two daughters, four grandchildren, six great-grandchildren, and a sister.